The evidence of environmental breakdown in Northern Ireland is overwhelming. It is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world, with 12 per cent of species here threatened with extinction (Gilbert et al., 2023). It is home to the largest freshwater lake in the UK and Ireland, which is visibly dying through the spread of blue-green algae. Such devastation is the norm, not the exception. Only 14 per cent of Northern Ireland’s lakes could be classified as having good ecological status in 2021 – down from nearly a quarter in 2015. The scandal of these statistics is compounded by comparison with the targets that were set for Northern Ireland to avoid environmental catastrophe. In the case of waters like Lough Neagh, that target is 100 per cent good ecological status by 2027. And we are meant to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Between 1990 and 2022, the UK as a whole managed a 50.2 per cent reduction in emissions; by comparison, the figure for Northern Ireland in the same period was a mere 26.4 per cent reduction (DAERA, 2024). For all the protests, podcasts and political pontificating, there appears to be a frustrating – and perilous – lack of action. This is not only due to the peculiarities of our political system; public opinion plays a part too. People will only make the behavioural, social and economic adjustments required to tackle climate change if they accept that, as things stand, they are in some way contributing to the problem.

In a new Research Update based on data from the 2024 Northern Ireland Life and Times (NILT) survey, we explored the public’s belief in climate change, as well as their sense of urgency and responsibility in addressing it. 59% of NILT respondents believed that climate change to be caused mainly or entirely by human activity. However, only 45% of unionists think this, compared to 68% of nationalists and 67% of those identifying as ‘neither’ unionist nor nationalist. Nevertheless, when we add in those who think that it is caused about equally by human activity and natural processes (27% overall), we see a clear majority across the board. Then, 78% unionists and 92% of both nationalists and those identifying as ‘neither’ think that human activity is a contributing factor to climate change. This overall figure of 86% is lower than the European average (91%), but it does mean that a clear majority of the Northern Ireland public in principle think that tackling climate changes requires change in human activity.

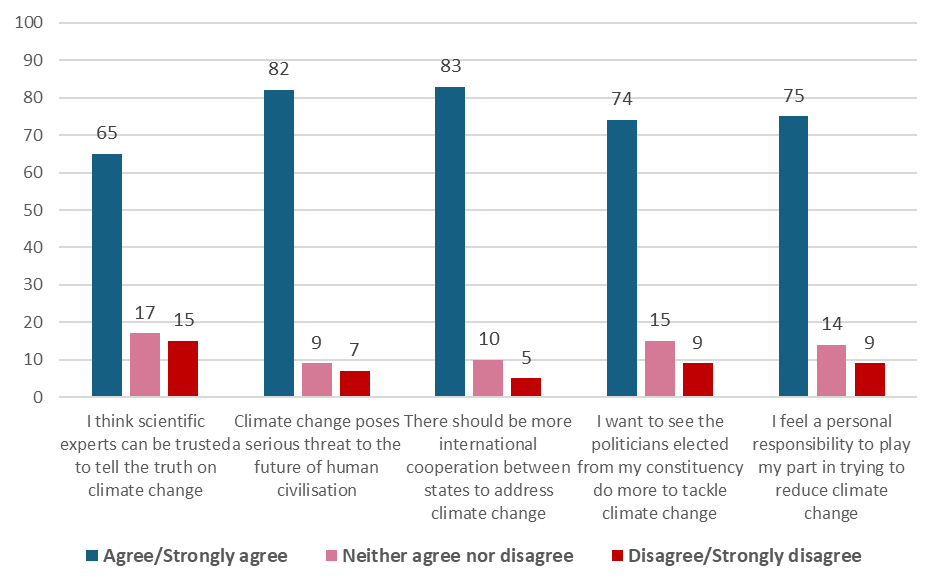

The question then becomes one of why such change is so sluggish in Northern Ireland. This is where other attitudes come into play (see Figure 1). There is more support among NILT participants for international cooperation between states to address climate change (83%) than support for local political action (74%). On this point, there are further differences among political communities (with only 60% of unionist respondents wanting to see elected politicians act on this issue), but it still constitutes a sizeable majority across constituencies. Notably, the figure on those wanting political action on climate change is the same for those from both rural and urban areas in Northern Ireland.

Where there is an apparent rural/urban divide, however, is on the fundamental question of whether scientific experts can be trusted to tell the truth on climate change; 67 per cent of respondents from urban areas agree/strongly, compared to 62 per cent of those from rural areas. Speaking at an ARK event on the launch of this data in May 2025, Kate Clifford (Director, Rural Community Network) explained the context for this. She recalled a farmer noting the shifting sands of government and expert guidance that the farming community has been told to follow in recent decades: to use pesticides/to avoid them; to remove hedges/to plant hedges; to have stream buffer strips/to minimise them. It is a reminder that enabling coordinated action to address climate change will require consistency and clarity in government messaging and incentivisation – something sorely lacking to date.

Figure 1: Attitudes towards climate change and means of addressing it (%)

The fact that only two thirds (65%) of NILT respondents overall trust scientific experts to tell the truth on climate change should ring alarm bells in itself. A lack of trust in authorities and experts relates to deeper trends which undermine the assumptions and functions of liberal democracy. Climate change disbelief is, according to the sociologist Christiane Lübke, ‘part of a broader, cross-national ideology’ characterised by opposing ’the mainstream’, including on such matters as immigration, pluralism and globalisation. The socio-political problem of a lack of trust in scientific expertise is a crucial contributing factor to climate crisis. What is more, it shows how the health of our planet is intimately connected to the health of our democracy. In Northern Ireland, the scale of the challenge is all too evident.

About the authors

Professor Katy Hayward MRIA FAcSS is Professor of Political Sociology and Co-Director of the Centre for International Borders Research at Queen’s University Belfast.

Dr Jonny Hanson is Research Fellow at Queen’s University Belfast and is ARK’s Assistant Survey. He researches the social aspects of climate, conservation and agriculture, and how these relate to other social processes and policies.

Dr Paula Devine is Co-director of ARK, and director of the Northern Ireland Life and Times survey.